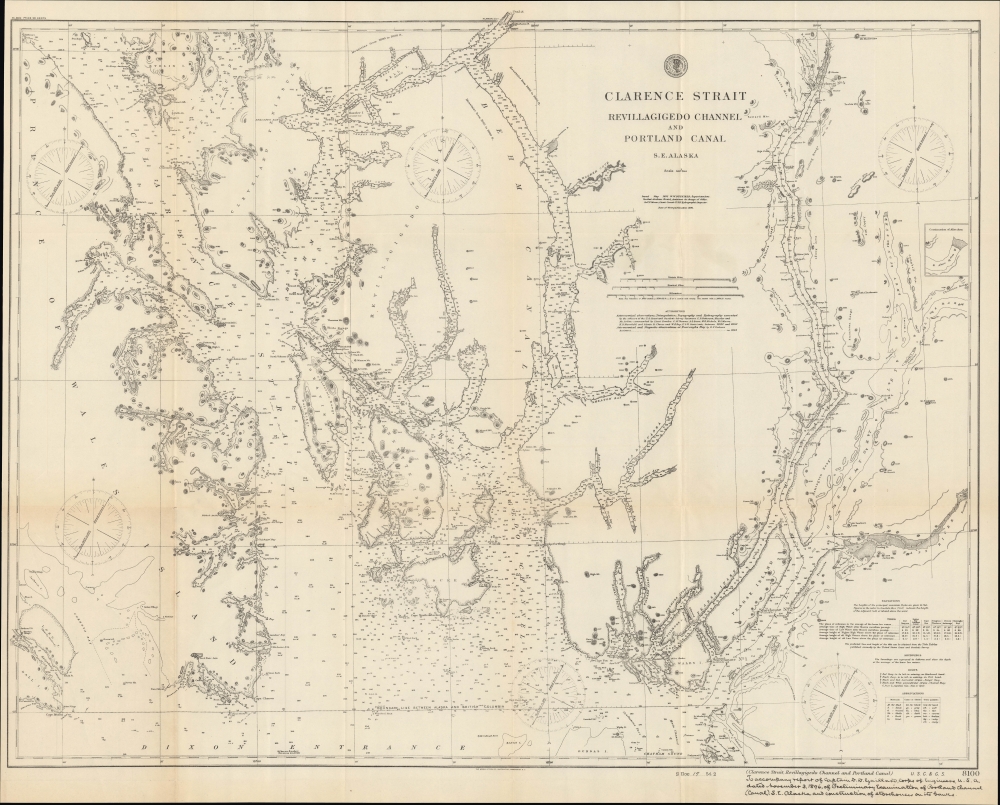

1895 U.S. Coast Survey Chart of Clarence Strait, Southeast Alaska, and Environs

ClarenceStrait-uscs-1895

Title

1895 (dated) 23 x 28.5 in (58.42 x 72.39 cm) 1 : 300000

Description

A Closer Look

Coverage ranges from Prince of Wales Island at left to the Portland Channel, Nass River, Somerville Island, and Port Simpson (now Lax Kwʼalaams) at right. Soundings, shoals, islets, buoys, and other features are noted throughout, along with coastal terrain and areas of high elevation (noted in feet). Coastal settlements, such as they were, including 'Kitchikan P.O.,' and storehouses are indicated. Additional information is provided on magnetic variations, soundings, tides, and more. A dashed line traces the boundary between Alaska and British Columbia along the lines proposed by the U.S., which closely resembles the ultimate border, the only difference being the inclusion of Wales Island and Pearse Island in British Columbia.The Alaska Boundary Dispute

The southern boundary of Alaska, even during the era of Russian rule, had never been concretely defined. Russia and Britain signed a treaty in 1825 defining the borders of their respective possessions, but these were vague at best. When the United States bought Alaska in 1867, the boundary was still ambiguous, and when British Columbia joined the new Canadian Confederation in 1871, the Canadian government requested a survey of the boundary between British Columbia and Alaska. The U.S. dismissed the idea, stating that it was too costly, and added that the area was remote, sparsely populated, and without any economic or strategic interest. This status quo changed in 1898 when gold was discovered in the Yukon.With the discovery of gold, Canada wanted to establish an all-Canadian route from the gold fields to a seaport. The U.S., however, did not agree, and prevented Canadians from staking a land claim near the coast to help sway any future decision with regard to setting the border. Tens of thousands of Americans moved into the region, greatly disturbing the Canadian government, which dispatched a detachment of North-West Mounted Police to the area to secure the border. But they were forced to retreat in the face of overwhelming numbers of gold seekers, taking up new fortified positions in two key mountain passes, complete with Gatling guns, in order to enforce the Canadian point of view. American officials, however, believed that the Canadian police had set up their roadblocks at least twelve miles inside American territory. This misunderstanding led to the establishment of the Joint High Commission of 1898-99, which was given the task of diffusing the situation and establishing a concrete border.

After months of discussions, the commission sent a treaty to the U.S. Senate, which was promptly rejected, because Western U.S. states did not like it. Eventually, negotiations resulted in the Hay-Herbert Treaty, which was signed and ratified by the Senate in 1903. Even then, however, the treaty only established a new body, the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal, to arbitrate the dispute rather than resolve the dispute itself. Composed of three American, two Canadian, and one British statesmen, the tribunal finally settled a boundary, mostly along the lines favored by the U.S. Canadians at the time were incensed that the British representative on the panel, Richard Everard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, typically sided with the Americans. The feeling was that his decisions were primarily motivated by British wishes to maintain a good relationship with the U.S. at the expense of Canadian interests. Subsequent historians have deemed the tribunal to have been generally fair, though the settling of a boundary in the Portland Channel, seen at right here, has been criticized as lacking legal standing and merely being a neat compromise over an intractable disagreement.

Publication History and Census

This chart was originally produced by the U.S. Coast Survey in 1891 and here is updated to 1895. A handwritten note at bottom-right indicates that it accompanied an 1896 report by Captain David du Bose Gaillard of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (more famous for his later contribution to the Panama Canal), who had been secretly dispatched by the U.S. Army to conduct a survey of the Portland Channel. The storehouses present on the chart were built by his team, unbeknownst to the Canadian authorities. The notation at bottom 'S Doc 19 54 2' and the printing by Norris Peters, a common printer of Congressional reports, indicate that Gaillard's updates to the 1895 chart along with his report were printed (photolithographed) as part of a group of Senate documents on the boundary dispute, likely with the treaty presented by the Joint High Commission mentioned above. It was also later reprinted as part of contending British and American atlases presented to the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal (Rumsey 0009.073).These three printings have seemingly been listed together in the OCLC, but in any event the map is independently cataloged by Stanford University, California State University Fresno, the Vancouver Public Library, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library, and the Boston Public Library.

CartographerS

The Office of the Coast Survey (1807 - present) founded in 1807 by President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of Commerce Albert Gallatin, is the oldest scientific organization in the U.S. Federal Government. Jefferson created the "Survey of the Coast," as it was then called, in response to a need for accurate navigational charts of the new nation's coasts and harbors. The spirit of the Coast Survey was defined by its first two superintendents. The first superintendent of the Coast Survey was Swiss immigrant and West Point mathematics professor Ferdinand Hassler. Under the direction of Hassler, from 1816 to 1843, the ideological and scientific foundations for the Coast Survey were established. These included using the most advanced techniques and most sophisticated equipment as well as an unstinting attention to detail. Hassler devised a labor intensive triangulation system whereby the entire coast was divided into a series of enormous triangles. These were in turn subdivided into smaller triangulation units that were then individually surveyed. Employing this exacting technique on such a massive scale had never before been attempted. Consequently, Hassler and the Coast Survey under him developed a reputation for uncompromising dedication to the principles of accuracy and excellence. Unfortunately, despite being a masterful surveyor, Hassler was abrasive and politically unpopular, twice losing congressional funding for the Coast Survey. Nonetheless, Hassler led the Coast Survey until his death in 1843, at which time Alexander Dallas Bache, a great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin, took the helm. Bache was fully dedicated to the principles established by Hassler, but proved more politically astute and successfully lobbied Congress to liberally fund the endeavor. Under the leadership of A. D. Bache, the Coast Survey completed its most important work. Moreover, during his long tenure with the Coast Survey, from 1843 to 1865, Bache was a steadfast advocate of American science and navigation and in fact founded the American Academy of Sciences. Bache was succeeded by Benjamin Pierce who ran the Survey from 1867 to 1874. Pierce was in turn succeeded by Carlile Pollock Patterson who was Superintendent from 1874 to 1881. In 1878, under Patterson's superintendence, the U.S. Coast Survey was reorganized as the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (C & GS) to accommodate topographic as well as nautical surveys. Today the Coast Survey is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or NOAA as the National Geodetic Survey. More by this mapmaker...

Norris Peters (c. 1834 – July 15, 1889) was a Washington D.C. based photo-lithographer active in the late 18th and early 19th century whom Scientific American called 'one of Washington's most eccentric and mysterious figures.' Peters was born and educated in Pennsylvania. He relocated as a young man to Washington D.C. where he took work as an examiner for the United States Patent Office. During his work with the patent office he became fascinated with the emergent process of photolithography. In 1869 Peters secured substantial venture capital of about 100,000 USD from an unknown investor and founded The Norris Peters Company at 458 Pennsylvania Avenue. Their printing offices have been described as 'unequaled in this or any other country.' From these offices Peters pioneered the development of American photo-lithography. For nearly a generation he held a near monopoly on government photo-lithographic printing. Among their more notable contracts included numerous maps for congressional reports, maps of the U.S. Coast Survey, maps of the U.S. Geological Survey, Mexican currency for the State of Chihuahua, and the Official Gazette of the Patent Office. Peters also maintained an interesting social life and was a confidant to many of the most powerful figures in Congress. He was also a bon vivant known for being an excellent cook and hosting lavish dinners, the invitations to which were 'never declined'. Despite being socially active he never married and died a confirmed bachelor. Following Peters' death in 1889 his business was taken over by Henry Van Arsdale Parsell who administered it until his own death in 1901. The company then merged with Webb & Borcorselski, another D.C. lithography firm, and was renamed Webb & Borcorselski-Norris Peters. They continued to publish under this name well into the mid 20th century. Learn More...

David du Bose Gaillard (September 4, 1859 – December 5, 1913) was an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers best known for his work on the Culebra Cut, which for many years was known as the Gaillard Cut, the most difficult portion of the Panama Canal. Born in South Carolina, Gaillard attended West Point and graduated in 1884. In 1896, Gaillard was secretly dispatched to Alaska to survey the disputed Portland Channel, one of the most contentious points in the Alaska Boundary Dispute between the U.S. and Canada. In 1908, he was tasked with devising a route through the Continental Divide portion of the Panama Canal, the most difficult portion of the entire project. He was regarded to have been an extremely hard-working officer who checked minor details of the project's expenses, saving millions of dollars in the process. Soon after returning from Panama in late 1913, Gaillard died of a brain tumor, not living to see the canal's opening. The Culebra Cut was named in his honor for most of the history of the canal's existence, but was returned to its original name when management of the canal was handed over to the Panamanian government. Learn More...